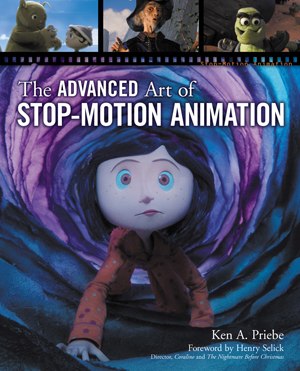

In the latest excerpt from The Advanced Art of Stop-Motion Animation, Ken A. Priebe continues his lesson on building puppets, focusing on puppet anatomy.

Buy The Advanced Art of Stop-Motion Animation by

Puppet Anatomy

For this section of the book, I’m pleased to present a look behind the scenes of some puppets created by Bronwen Kyffin and Melanie Vachon for a student film directed by Lucas Wareing at Emily Carr University of Art + Design in Vancouver. Lucas took my stop-motion course at VanArts several years ago and more recently directed his own stop-motion short at Emily Carr called Ava, which was about the relationship between a little girl named Ava and her monster friend, Charlie. These characters (Figure 3.34) were designed by Patrick O’Keefe and commissioned to Bronwen and Melanie for fabrication, with the assistance of Ian Douglas in machining the armatures. Certain elements of their construction in relation to silicone molding and plastic casting will be detailed further a few pages later, but for now here is a look at how the general fabrication was done. (Except where noted, all photos in this section are courtesy of Bronwen Kyffin and Melanie Vachon.)

Both puppets were built out of metal ball-and-socket armatures (Figure 3.35), which are the strongest type of armatures for stop-motion and provide a great deal of precision and control over the animation. These types of armatures were certainly necessary considering that Charlie himself was about 16 inches tall (next to the 9-inch-tall Ava), and wire definitely would not have supported his bulk and weight. Charlie’s armature (Figure 3.36) was also equipped with chest and waist blocks that were cast in plastic. These blocks were designed to create more leverage with his eventual bulk, cut down on his weight, and give his skin something to hold onto. The blocks were screwed onto the armature with long threaded rods attached to the aluminum chest and waist plates, which had additional holes drilled into them (like Swiss cheese) to cut down further on the puppet’s weight.

Ball-and-socket armatures consist of many different kinds of joints that can be created. The joints most commonly revolve around a sandwich plate. The plate consists of two long, oval-shaped metal plates with holes drilled into them that wrap snugly around a ball bearing but are loose enough to move into increments. The sandwich plate can also be a U-shaped joint that is about half the size and shape of a full joint. The ball bearing serves as the joint and has a hole drilled into it, into which a metal rod for the limb is inserted and brazed together with a blowtorch. It is possible to buy threaded rods and ball bearings that are already drilled and tapped with threaded holes for this purpose.

When designing joints like these, it is important to think ahead to the actual animation and motion that are required, in terms of which joints need to move forward and backward, up and down, or any range of diagonal movement. Ball joints typically provide a great range of circular movement compared to hinge joints, which typically only have lateral movement up and down, like a knee or elbow. In the close-up detail of Charlie’s torso (Figure 3.37), there are three U-shaped joints: one for each shoulder and a middle one for the neck. These joints are the anatomical equivalent of the clavicle and the point where the neck joins the spine. The range of movement for these ball joints is mostly left/right or up/down, which allows for tilts of the head and shrugs of the shoulders. The location of the plates in relation to the rod means a small amount of forward/backward motion is possible. However, there is more freedom of movement allowed for in the joints on the other end of the rod, which provides additional mobility for his neck and shoulders. The same principles of motion are applied to the leg joints, based on how they should be able to move (Figure 3.38). When the parameters of movement are specified in terms of the amount of freedom needed in the animation, these parameters can be applied directly to how the armature is constructed. The more you know about real human anatomy and how real joints are capable of moving, the more informed the armature can be in terms of mimicking this motion for animation. If you have any experience in rigging 3D computer models, you may find some similarities to the necessary constraints of movement involved, but the biggest difference is dealing with real physical materials.

Both puppets’ armatures are covered in foam that is carved into shape to provide the bulk of their bodies. First, two blocks of foam are spray glued to each other around the front and back of the armature (Figure 3.39 and 3.40).

The excess foam is simply carved and snipped away until the foam takes on the desired shape. Large pieces are carved out to start, and then smaller pieces are snipped away with scissors (Figure 3.41). For Charlie, the same method is applied to his arms (Figure 3.42). In addition to his foam body, his hands are cast in silicone and his head in plastic. (More detail on these techniques will be explored later in this chapter). The outer layer of Charlie is then skinned in fabric by cutting out patterns according to his shape and stitching them together (Figure 3.43). For the striped pattern on his skin, masking tape is applied to his body in a specifically designed pattern (Figure 3.44), and the exposed parts are airbrushed lightly with white paint. When the tape is removed, the original darker color of the fabric remains in these areas to create stripes (Figure 3.45). With all of these steps completed, Charlie’s body is essentially complete. Topping him off are replacement pieces for his eye and lip sync movements, which are made of Sculpey. His eyes are coated with Vaseline on the back to allow them to stick to his plain white eyeballs, and his lips are attached to his head with double-sided tape (Figure 3.46).

Ava’s hands are constructed with aluminum wire to fit to shape under her fabric mittens (Figures 3.47 and 3.48). Her head is coated with primer, and her eyes (as well as Charlie’s) are masked apart from the rest of her face and sprayed with Crystal Clear high-gloss acrylic to give them a smooth shine and finish (Figure 3.49). Next, her eyes are masked and the rest of her face exposed so it can be airbrushed with a skin tone (Figures 3.50 and 3.51). Additional paint and doll hair complete the necessary detail on her head (Figure 3.52). The final steps are to sew together tiny clothes in fabric over her body (Figure 3.53) and cast silicone boots to fit over her feet (Figure 3.54). She also has a tiny backpack made of canvas, with a tiny snap rivet holding in a roll of fun foam (Figure 3.55). Her pupils and replacement mouths, which can be attached, moved around, and removed from the plastic head with Vaseline, complete her facial expressions (Figure 3.56), and she is ready for animation (Figure 3.57)!

Ken A. Priebe has a BFA from University of Michigan and a classical animation certificate from Vancouver Institute of Media Arts (VanArts). He teaches stop-motion animation courses at VanArts and the Academy of Art University Cybercampus and has worked as a 2D animator on several games and short films for Thunderbean Animation, Bigfott Studios, and his own independent projects. Ken has participated as a speaker and volunteer for the Vancouver ACM SIGGRAPH Chapter and is founder of the Breath of Life Animation Festival, an annual outreach event of animation workshops for children and their families. He is also a filmmaker, writer, puppeteer, animation historian, and author of the book The Art of Stop-Motion Animation. Ken lives near Vancouver, BC, with his graphic-artist wife Janet and their two children, Ariel and Xander.

![[Figure 3.34] Puppets for Ava, a film by Lucas Wareing. (l) [Figure 3.35] Ball-and-socket armatures for Ava and Charlie. (c) [Figure 3.36] Armature for Charlie, the monster. (r) [Figure 3.34] Puppets for Ava, a film by Lucas Wareing. (l) [Figure 3.35] Ball-and-socket armatures for Ava and Charlie. (c) [Figure 3.36] Armature for Charlie, the monster. (r)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/featured/46091-advanced-art-stop-motion-animation-building-puppets-part-2.jpg?itok=wv7XUe1Q)

![[Figure 3.37] Close-up detail of Charlie’s chest armature. [Figure 3.37] Close-up detail of Charlie’s chest armature.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0337.jpg?itok=iFFiefnr)

![[Figure 3.38] Close-up detail of Charlie’s feet armature. [Figure 3.38] Close-up detail of Charlie’s feet armature.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0338.jpg?itok=i3f9apc2)

![[Figure 3.39] Ava and Charlie’s armatures laid over blocks of foam. [Figure 3.39] Ava and Charlie’s armatures laid over blocks of foam.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0339.jpg?itok=GwEgJMSE)

![[Figure 3.40] Two foam blocks glued over the armature on the front and back. [Figure 3.40] Two foam blocks glued over the armature on the front and back.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0340.jpg?itok=TOpqOFfU)

![[Figure 3.41] Ava’s carved foam body on the left, and Charlie in progress on the right. [Figure 3.41] Ava’s carved foam body on the left, and Charlie in progress on the right.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0341.jpg?itok=fmgq-yJo)

![[Figure 3.42] Continuing to carve and cut away the foam for Charlie’s arms. [Figure 3.42] Continuing to carve and cut away the foam for Charlie’s arms.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0342.jpg?itok=oxt6eKsk)

![[Figure 3.43] Charlie being skinned in fabric. [Figure 3.43] Charlie being skinned in fabric.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0343.jpg?itok=UhZ9E-bB)

![[Figure 3.44] Creating shapes for Charlie’s stripes using masking tape. [Figure 3.44] Creating shapes for Charlie’s stripes using masking tape.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0344.jpg?itok=6SuF2naE)

![[Figure 3.45] Peeling the tape away after airbrushing the fabric. [Figure 3.45] Peeling the tape away after airbrushing the fabric.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0345.jpg?itok=ewHD2iON)

![[Figure 3.46] Eye pieces and replacement mouths for Charlie. [Figure 3.46] Eye pieces and replacement mouths for Charlie.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0346.jpg?itok=cHiU4RO8)

![[Figure 3.47] Wire hand for Ava laid over the character design diagram. [Figure 3.47] Wire hand for Ava laid over the character design diagram.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0347.jpg?itok=B1YS4bwf)

![[Figure 3.48] Wire hand inside real hand, for comparison of scale. [Figure 3.48] Wire hand inside real hand, for comparison of scale.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0348.jpg?itok=cRjTnP0X)

![[Figure 3.49] Masking the head and exposing the eyes for coating. [Figure 3.49] Masking the head and exposing the eyes for coating.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0349.jpg?itok=Xu-vm4Dt)

![[Figure 3.50] Beginning to mask the eyes so that the rest of the head can be painted. [Figure 3.50] Beginning to mask the eyes so that the rest of the head can be painted.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0350.jpg?itok=x6XaPoiG)

![[Figure 3.51] The head after being airbrushed. [Figure 3.51] The head after being airbrushed.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0351.jpg?itok=KJHBIHG3)

![[Figure 3.52] The head with hair and painted details added. [Figure 3.52] The head with hair and painted details added.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0352.jpg?itok=c81dUl68)

![[Figure 3.53] Sewing clothes over the armature. [Figure 3.53] Sewing clothes over the armature.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0353.jpg?itok=klEBJkdG)

![[Figure 3.54] Additional clothing and boots are added on. [Figure 3.54] Additional clothing and boots are added on.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0354.jpg?itok=312h84VW)

![[Figure 3.55] Ava’s little backpack. [Figure 3.55] Ava’s little backpack.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0355.jpg?itok=8l30plV_)

![[Figure 3.56] Completed Ava puppet, with eye pieces and [Figure 3.56] Completed Ava puppet, with eye pieces and](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0356.jpg?itok=irGiJgc_)

![[Figure 3.57] Charlie and Ava together in a scene from the film. (Courtesy of Lucas Wareing.) [Figure 3.57] Charlie and Ava together in a scene from the film. (Courtesy of Lucas Wareing.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/46091-stop-motion-ch3-2-fig0357.jpg?itok=zs6x3D9y)